When someone says they hate your product with a burning passion

What CodeRabbit did, and what to do instead

Let’s say you get negative feedback in public. It’s blunt, even abrasive. You instinctively bristle: they’re wrong, they don’t get it, they’re trolling. So naturally, you push back. But your rebuttal only makes the critic double down, and now others are piling on. You clarify your position, but it only gets worse.

Why does this happen, and what can you do about it?

Feedback is a regulatory mechanism

Imagine a thermostat for your credibility. People form an opinion on what the correct setting should be, and they regulate if the reality seems off. If you’re above their setpoint, people feel you’re overrated and want to bring you down; if you’re below it, people feel you’re underrated and want to build you up. And the farther off you are, the more they’ll overcorrect.

When someone is frustrated with you (or your company, or your product), they have a view of how much you should be dinged for something. Venting in public is a way to regulate your reputation and achieve the proper homeostasis, like turning a thermostat toward the desired setting.

This means that the substance of someone’s feedback is totally separate from their frustration or desire to be heard. Complaints often seem unfair and you might want to jump to fact checking, but that won’t get anywhere unless you first resolve the frustration and make people feel that you actually listened. (It turns out facts do care about our feelings.)

Resistance is escalation

When you reject someone’s feedback, you’re implying that (1) they’re wrong, (2) they’re possibly dumb, and (3) they don’t have the authority to judge you.

To be clear, sometimes that’s all true and you need to fight or ignore. But in this case, we’re focusing on substantive feedback from people who matter, like your customers.

By rebutting, you’re forcing them to justify and defend their initial statements. Either they were wrong to raise it or you were wrong to resist! Their choice is obvious.

Now their move is to escalate further, maybe with more examples or stronger language. As this plays out, onlookers will tend to take the critic’s side, as an angry customer is more relatable than an imperious founder.

Aiden v. CodeRabbit

Going back to the thermostat analogy, a stubborn dial only makes people twist harder.

Here’s a recent example.

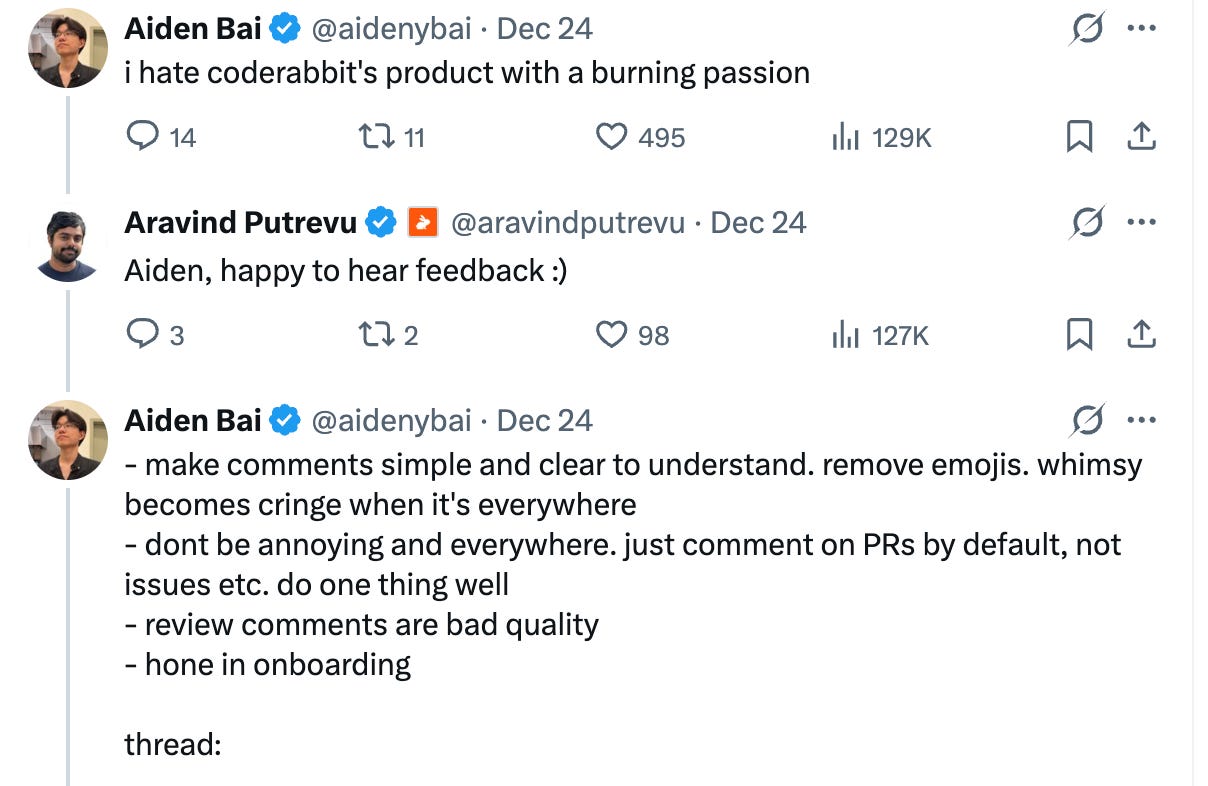

Last week, Aiden Bai posted about grievances with CodeRabbit. Pretty normal so far; users complain about products all the time. A CodeRabbit engineer jumped in to ask for feedback, which was good, and Aiden followed up with details (full context here):

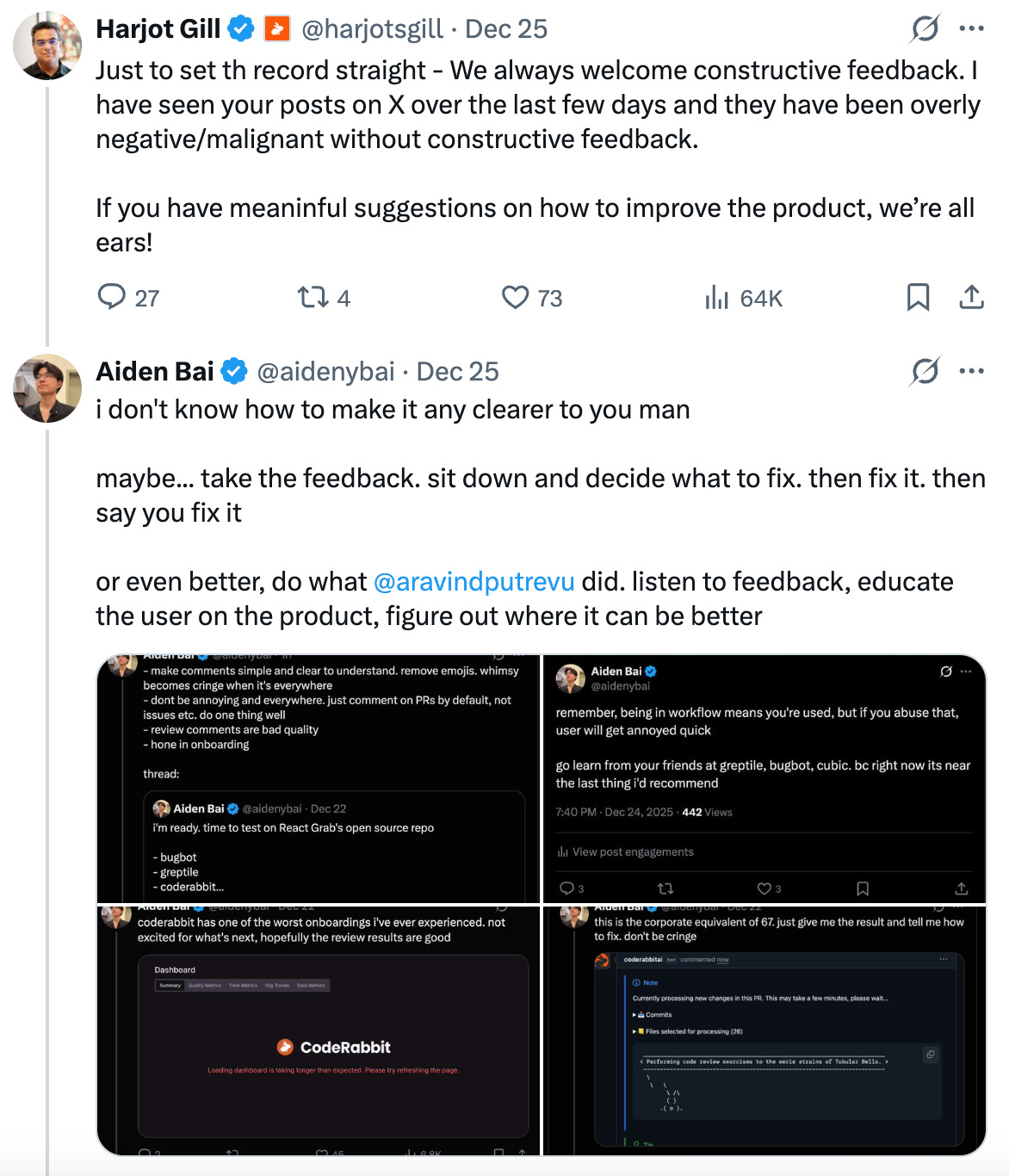

CodeRabbit’s CEO, Harjot, then entered the chat:

In one post, he

called his own customer clueless,

then implied CodeRabbit had enough users that this feedback didn’t matter,

then condescendingly speculated that, even if it were valid, it could probably be solved by “simpler controls and a lot of handholding,”

then, to gild the lily, made sure to insult not only Aiden personally but indie developers as a category.

Now, we should remember that writing a bad response isn’t the same as being a bad person. Harjot was frustrated by what he felt was a bad faith attack on his company, and I have a lot of sympathy for founders getting hater-fatigue.

Nonetheless, the response was objectively not good, and what came next was predictable:

The net upshot was bad vibes for CodeRabbit and a layup for its competitors:

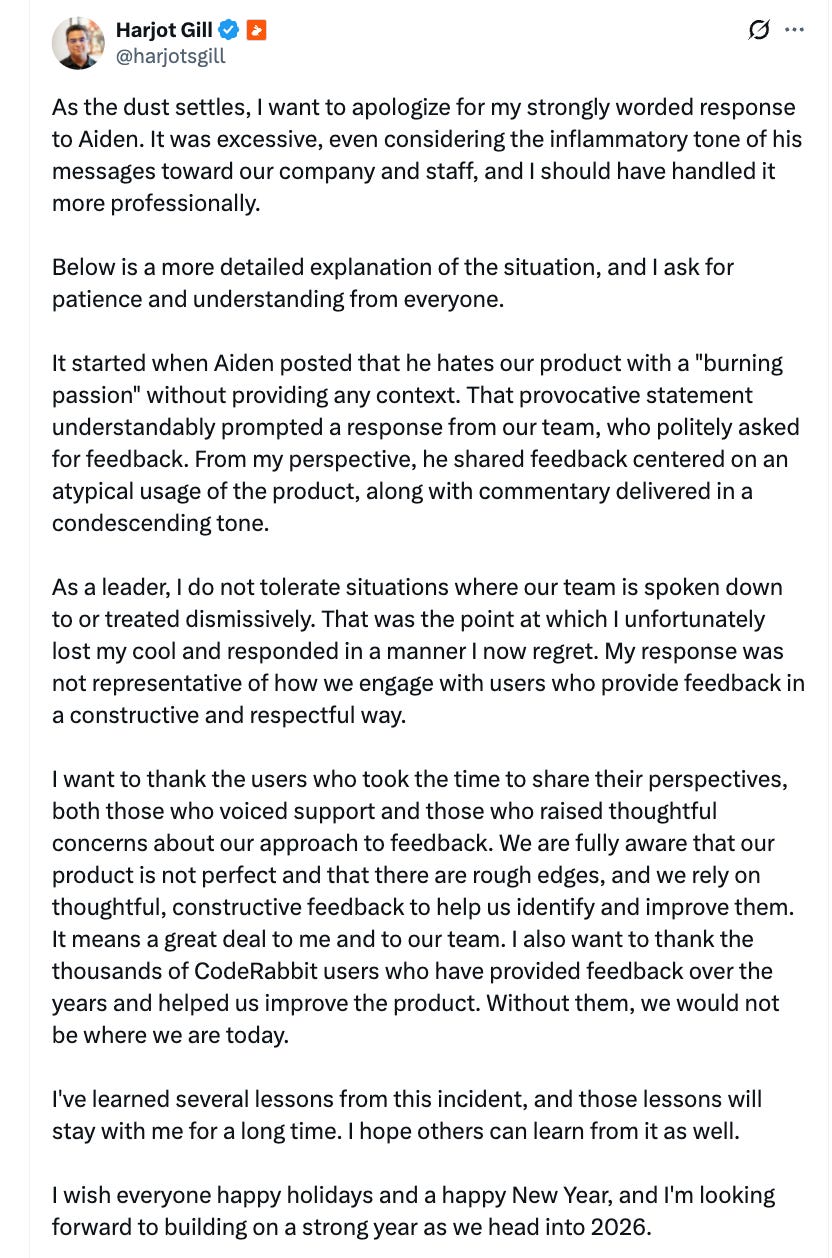

The episode finally ended with an apologish from Harjot:

My advice for this kind of post is to pick a lane: if it’s an apology, make it a proper one and resist the urge to sprinkle in more veiled jabs. You could also take the other route and just not apologize. It’s best to try avoiding any uncanny valley situations. But it happens: bad interactions are unavoidable and this one wasn’t too damaging in the grand scheme.

How to reset

As Tolstoy would’ve said, all positive mentions are alike; every negative mention is irksome in its own way. It varies based on who’s involved, what the feedback is, how much traction it’s getting, etc. etc. etc. — there isn’t a universal solution. As I’ve noted, sometimes it really is bad faith trolling, and that calls for a very different approach.

But in general, as a founder you should be your own hardest critic. You should have a higher standard for yourself than anyone else could possibly impose. You should be voracious for user feedback, even if it feels unfair.

And the magical thing is, when you sincerely feel that way and you demonstrate it, criticism tends to wilt.

Imagine a scenario where you get negative feedback, and you overrule the instinct to push back. Instead, you listen to the feedback, you embrace the responsibility to make the best product possible, you even thank them for caring enough to share their thoughts (remembering that your real enemy isn’t negativity but indifference).

With just this, you’ll have shown more curiosity, more ownership, more humility than they were even hoping to enforce. They’re surprised to find that the imbalance is now in the other direction. Instead of feeling snubbed or dismissed, they might consider whether their initial jab was excessive. They now risk overcorrecting and overshooting the setpoint they were aiming for.

And when people feel they’ve gone too far, they restore balance by pulling back. It’s common to see someone gearing up for a confrontation but, upon finding the other person gracious and receptive, pivot to, “Thanks for sharing the context,” “I shouldn’t have overreacted,” “I appreciate how you handled this, “I do like the product overall,” or some other form of deescalation — maybe even an apology or retraction.

Claude gets it!

TL;DR

When getting negative feedback:

Separate the information part from the emotion part. There’s the substance of the feedback, and there’s the customer’s frustration and expectation of being heard. Those are discrete, and you can’t address the former without resolving the latter.

Start by aligning on principles, before rushing to defend yourself. Whatever the merits of the feedback, you agree that quality is important, that feedback is valuable, and that the feedback has found the person who’s responsible. Again, there’s no hope of aligning on facts if you can’t first align on principles.

Make a point of overindexing on accountability. Take more responsibility than what seems necessary. Take so much ownership that it surprises people. This obviates their need to hector you over it and removes a lot of surface area for attack, creating space for a calmer exchange. More importantly, if you’re the founder, the reality is that every detail of your product does fall on you.

If you need to clarify facts, explain instead of defending. You can share the exact same information in a way that’s either defensive and caustic, or earnest and transparent. The only difference is tone.

If self-critique or apology is warranted (it isn’t always), keep it straightforward. No need to grovel or self flagellate. Recap the problem plainly, explain the fix, say what you’re doing to prevent it in the future, and wrap it up. Then move on.

I love this post. It's a masterclass in what to do. Yet every founder reads advice like this. every founder nods along then every founder does the exact opposite when it happens to them. I've seen this happen over and over.

I really enjoyed this post. Wrt the first tldr ("Separate the information part from the emotion part."), I've worked with soooo many people who intellectually know this is what they should do, but in practice find themselves blocked from doing it. It's wonderful to watch them unlearn those blocks: they start effortlessly following this advice!